Construction material – possibly “manufactured sand” i.e. crushed granite – comes in on a barge into Singapore’s east coast, passing Changi Airport where an aeroplane had just taken off. Singapore, which has reclaimed about 20% more land from the sea since its 1965 independence, is continually short of sand, after buying it for years from its Southeast Asian neighbours. It is trying to devise construction alternatives that use less sand in anticipation for greater land needs as its population increases. (Manufactured sand: https://theconstructor.org/building/manufactured-sand-m-sand-in-construction/8601/)

ARTIST STATEMENT – Shifting Sands – Sim Chi Yin – June 2017

Singapore is the world’s largest importer of sand. (see reference links)

Why is that and what does that mean? What impact does that have on its neighbours? With rapid urbanisation and massive land reclamation around the world, there is now a growing global shortage of sand — a resource that, almost counter-intuitively, is finite. What does that mean for cities like Singapore, going forward? How should we view this piece of global story?

References: (http://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/visualize/tree_map/sitc/import/show/all/2733/2016/ ) (http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/strict-rules-in-place-for-import-of-sand-mnd).

slider

images not found

Photograph by Sim Chi Yin. Enroute to Punggol (2017)

ARTIST STATEMENT – Shifting Sands – Sim Chi Yin – June 2018

Shifting Sands (Singapore, Malaysia, China, 2017 – on-going)

The world is running out of sand. It seems counter-intuitive but the sand, besides air and water, is our most used commodity. The insatiable demand for this non-renewable resource has led to environmental impact where it’s mined and to mafias driving the lucrative business.

The global depletion of sand is driven by rapid urbanisation — especially in China and other parts of Asia — and land reclamation. Singapore, where I’m from, is the world’s largest importer of sand per capita. It has reclaimed almost a quarter of its territory over the last 60 years.

The story of sand is, to me, that of the global income gap writ large: wealthy states buy up land from their poorer neighbours and move it to where they want it.

I’ve mapped and researched this on-going project on this looming global problem. I’m seeking ways to work on it across several countries.

These early chapters of this on-going project, photographed in Singapore and Vietnam, were supported by Exactly Foundation, the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting, and National Geographic, and The New York Times Magazine.

NOTE: No part of ANY text and material related to Shifting Sands can be used, copied, published or quoted without written permission from the author(s).

ARTIST STATEMENT

Shifting Sands by Sim Chi Yin (January 2018)

Tong Thi Mong Trinh had just been lying in bed speaking on her mobile phone to her children who were visiting relatives. She said goodnight and hung up. From behind her, tree branches suddenly snapped loudly. Dogs howled and chickens squawked in panic. She jumped out of bed and moments later, watched her mattress float away, as the earth beneath her feet melted away into the river, and in to the darkness of night.

Recounting this to me five days after the landslide, Ms Tong, 27, a seamstress, was still too traumatised to even go anywhere near her old home – just 50 metres from where she has relocated now. Even the family dog, who fought its way out of the water that night, has been too frightened to enter the half eroded house.

Off Singapore’s westernmost coast, a series of beige mountains are rising out of the deep blue sea. Ships laden with mounds of sand spit their loads, making the mountains higher and higher. Singapore, long fed the narrative of being land scarce, is building what will become the world’s largest container port here over the next 30 years, by making land out of the sea as it has done since British times.

Every morning, a stream of flat-top barges chug in to Singapore waters past morning joggers and anglers at Changi Point, and make their way to Punggol terminal – a key place on mainland Singapore where the country receives and stores the sand used to augment its territory. Singapore, which has reclaimed about 20 per cent of its area since becoming an independent country in 1965, has had a long history of creating land out of the sea and swamps since British colonial times in the 1820s. It flattened many of its hills and ran out of its own supply of sand decades ago and has been buying sand from its Southeast Asian neighbours for reclamation and construction work. It is reportedly planning to reclaim another 6,200 hectares by 2030.

Where some of this sand comes from – the Mekong Delta in Vietnam – every day now, one and a half football fields worth of land is melting away into the Mekong River, say environmentalists. That is because of China’s damming of the river upstream and the rampant sand mining that is going on along the river. Locals I met lament the loss of their ancestral land and homes. While it is not clear what percentage of the sand dredged fuels Vietnam’s own building boom, Vietnamese press investigations have shown that some of those barges head to Singapore. This also shows up when we tracked marine traffic. Last year, an old artillery shell from the Vietnam war was found in a heap of sand in Tuas, reported The Straits Times.

The Singapore government has long tried to be quiet about where the tiny, wealthy island nation buys its sand from. When pushed by Cambodian NGOs in recent years, it has always maintained that it does not buy sand from dodgy suppliers. But in the long chain of this commodity changing hands from source to user, what is our responsibility to the people and lands further downstream?

In this highly lucrative sand trade (so attractive there are sand mafias), rich cities are developing at the expense of their poorer neighbours – the growing global income gap writ large. Seen another way, the wealthy are buying bits of territory and moving it where they want it.

Globally, it might seem counterintuitive, but we are running out of useable sand.

The material that goes into concrete, glass, computer chips and much else we use daily is becoming scarce. Massive worldwide urbanisation (especially in Asia and Africa) and land reclamation is driving this shortage.

Sand is already the natural resource we use more of than any other except water and air. The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) estimates global consumption at an average of 40 billion tons per year, with almost 30 billion tons used in concrete.

This thirst for sand is driving a craze to mine for it, in the sea, on land, in rivers, leading to a series of environmental repercussions, and impact on local communities and livelihoods. Beaches and river beds across the world – from as diverse places as Cape Verde, China and Vietnam — are being stripped bare. In Indonesia, more than 20 small islands are said to have disappeared because of sand mining. The UNEP report said the global sand business “is having a major impact on rivers, deltas and coastal and marine ecosystems,” although the trade “remains largely unknown by the general public.”

Sand depletion is a looming problem global problem and the story of our time. Within the vast landscapes of sand sucked up and new lands and territory created, people and their generations-old ways of life are being changed forever.

==============================

Exactly Foundation – Residency #6 – Shifting Sands by Sim Chi Yin (June 2017)

Word from the ‘Wart (Li Li Chung)

21st January 2018

As a citizen, I’ve been “fat, dumb and happy”.

I work hard, live well, pay taxes and don’t say much. I know of Singapore’s land reclamation since Raffles’ times. I know we had taller hills before. I can see the gleaming downtown skyline. I can see the massive sprouting of new HDBs. Shopping’s great, food’s even better.

But I can’t see the ethics of how “it” all came about. Specifically, I can’t see what it means for the environment or other countries’ economies, much less a fisherman’s livelihood (and that’s not a Singaporean fisherman, we don’t have any anymore).

I can’t see the not-so-visible and the not-so-conscious because it’s not-so-talked-about: questions such as what is really going on below the surface and away from our shores. I certainly didn’t fret much over where the material came from. I was just (still am) super proud and relieved coming home to our magnificent Changi Airport and riding past the Singapore Eye and Marina Bay Sands. I am fat, dumb and happy … and immensely grateful.

My London professor on hearing my interest in the Population White Paper debate (2013, when it was tabled in Parliament that Singapore’s population should grow 23% to 6.9 million by 2030, to ensure economic growth), aptly asked: “Where are they [additional people] going to live?” A Singaporean would probably then say: “Yah lor … exactleeeee” … and probably leave it at that. Should we … just leave it at that?

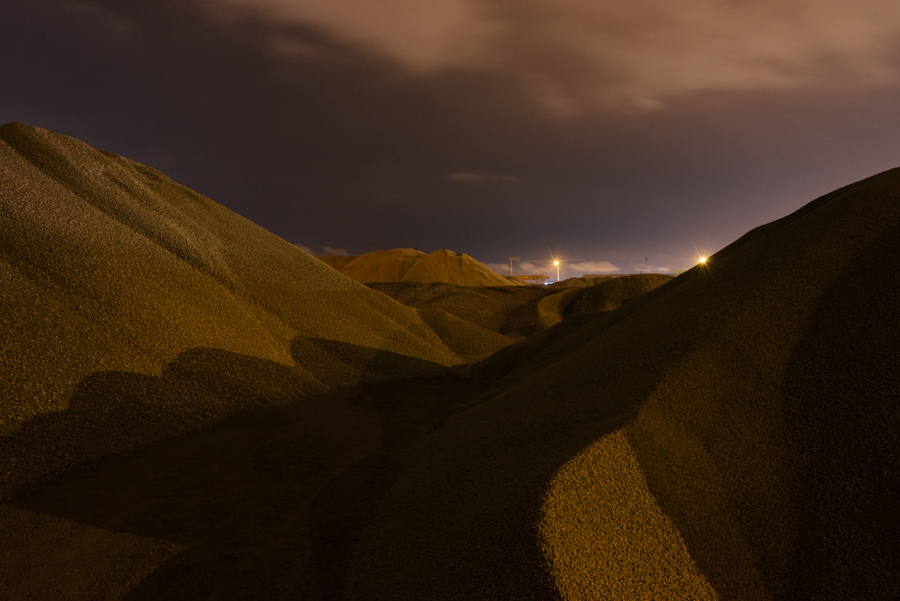

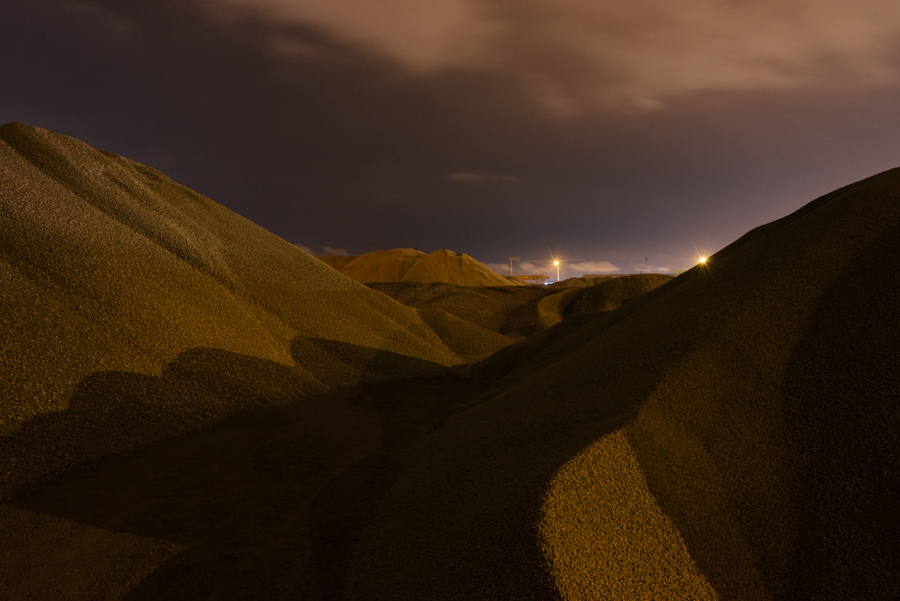

When I set up Exactly in 2015, a friend advised me to include Punggol; he said “you should see what’s going on there”. When he gave me a tour of the area, I asked him what it’s like to live in Punggol, his first comments: “it’s getting crowded … it’s really dusty”. I thought he meant dust from the ferocious building of new HDBs. He said, “No … you should see our sand dunes”. Sand dunes? And they are a sight to behold. In Exactly’s first inaugural project Northeast Hinterland by Kevin WY Lee, his capture of these dunes at night (below) is surreal, like a desert scene. Most viewers reacted with: “Is this Singapore?”

Photo by Kevin WY Lee. Sand Dunes. Taken during Exactly Residency June 2015

And so my fascination with sand started, particularly its political economy. I am thrilled that Sim Chi Yin, who is one photographer I hounded since Exactly’s early days to do a project, expressed interest in the “global sand shortage”. To get one’s head around a “sand shortage” requires overcoming surprise at every turn. I now know: there’s sand and there’s sand. It takes mental gymnastics to be educated on sand appropriate for building/landfills; one has to dig up (what a pun) information and research on just what it takes to reclaim land and fill it up with buildings and infrastructure. Not forgetting that Singapore is not alone doing this. Thus, we face a shortage of sand. Thus, it can get clandestine — one of the funniest phrases I heard is “smuggling sand” — how does one not see a 1000-ton barge cruising by with ill-gotten sand?

All this brings up the thorny issue of “borders”. Since the beginning of time, conflicts rage over territories and that usually means about land. Bigger is better, more powerful than small. Literally stakes in the ground, lording over land allows for control of people, resources and taxable rights to pass through, trade and live. We know that our borders today are recent constructs (post-WWII) that provide for messaging statehood and sovereignty. In reality, borders and resident groups may not match, such that languages and cultures cross borders seamlessly and often operate in a different paradigm. Even airspace control can confuse borders with “jurisdiction” from the 1940s remaining unchanged: I learned over a lunch break at Asia Research Institute’s symposium Borders, Mobilities and New Infrastructures in an Age of Shifting Power Configurations (January 2018) that Singapore regulates air traffic of commercial and military flights over Singapore and parts of Indonesia. So who owns what and how and why? The ultimate question for me: what is citizenship? In a quirky sort of way, Chi Yin’s Shifting Sands project stuns me into dumbfounded silence — what’s my say then?

Suggested Readings:

- Rachel Au-Yong. “Strict rules in place for import of sand: Government”. Straits Times 23rd January 2017. http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/strict-rules-in-place-for-import-of-sand-mnd

- Vince Beiser. “The World’s Disappearing Sand”. The New York Times, 23rd June 2016.

Bloomberg News. “The $100 Billion City Next to Singapore Has a Big China Problem”. Bloomberg 23rd June 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2017-06-22/the-100-billion-city-next-to-singapore-has-a-big-china-problem

- Joshua Comaroff. “Built on Sand: Singapore and the New State of Risk”. Harvard Design Magazine No.39. http://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/issues/39/built-on-sand-singapore-and-the-new-state-of-risk

- Rodolphe De Koninck. Singapore’s Permanent Territorial Revolution: Fifty Years in Fifty Maps. NUS Press May 2017

- Global Witness. “Shifting Sand: how Singapore’s demand for Cambodian sand threatens ecosystems and undermines good governance”. May 2010. https://www.globalwitness.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/shifting_sand_final.pdf

- Chappy Hakim. “A strange anomaly in management of airspace”. Straits Times 26th March 2016. http://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/a-strange-anomaly-in-management-of-airspace

- Lin DeRong. Strange Playgrounds: Scrambling Sands Servant Sands. https://situatingdomesticities.files.wordpress.com/2017/12/sd-workshop-document_lin-derong1.pdf. Vimeo: Scrambling Sands https://vimeo.com/244954980

- David Owen. “The World is Running out of Sand”. The New Yorker 29th May, 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/05/29/the-world-is-running-out-of-sand

- Luka Pauer. “Peak Sand: On the Limits of Resource Extraction Urbanisms in the Straits of Singapore”. Critical Planning 20: The Future, 2013, UCLA Urban Planning Department. http://www.academia.edu/7988126/

- Renuka Rayasam. “Even desert city Dubai imports its sand, this is why”. BBC5 May 2016. http://www.bbc.com/capital/story/20160502-even-desert-city-dubai-imports-its-sand-this-is-why

Hul Reaksmey. “Cambodia Bans Sand Exports From Province Over Environmental, Social Concerns”. VOA Khmer 13th July 2017. https://www.voacambodia.com/a/cambodia-bans-sand-export-from-province-over-environmental-social-concerns/3942750.html

Martha Soezean. “Govt downplays large gap of sand import and export of Cambodia and Singapore”. The Online Citizen,18th January 2017. https://www.theonlinecitizen.com/2017/01/18/govt-downplays-large-gap-of-sand-import-and-export-of-cambodia-and-singapore/

Samanth Subramanian (Photographs by Sim Chi Yin). “How Singapore Is Creating More Land for Itself”. The New York Times. 20th April 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/20/magazine/how-singapore-is-creating-more-land-for-itself.html