ARTIST’S STATEMENT December 2015

[NOTE: No part of ANY text and material related to Mute is to be used, copied, published or quoted without written permission from the author(s)]

Turning over every stone

Journey taken all alone.

I gave myself up for lost in the depth of a glad humiliation – in the shadow of a dim delight.

Artist Statement 19th March 2016

In 1973 when I was five years old, my mother was a nanny to a Japanese family. I recalled there were many Japanese expatriates staying in the west of Singapore, mainly along Pasir Panjang to West Coast Road.

For a year, I spent most my time with the Japanese family. During that time, I was attracted to Japanese popular culture, mainly manga or anime like Ultraman, Godzilla, Gatchamen, Astro Boy, etc. Cartoon series and popular culture was pretty much all I knew for a long time about Japan.

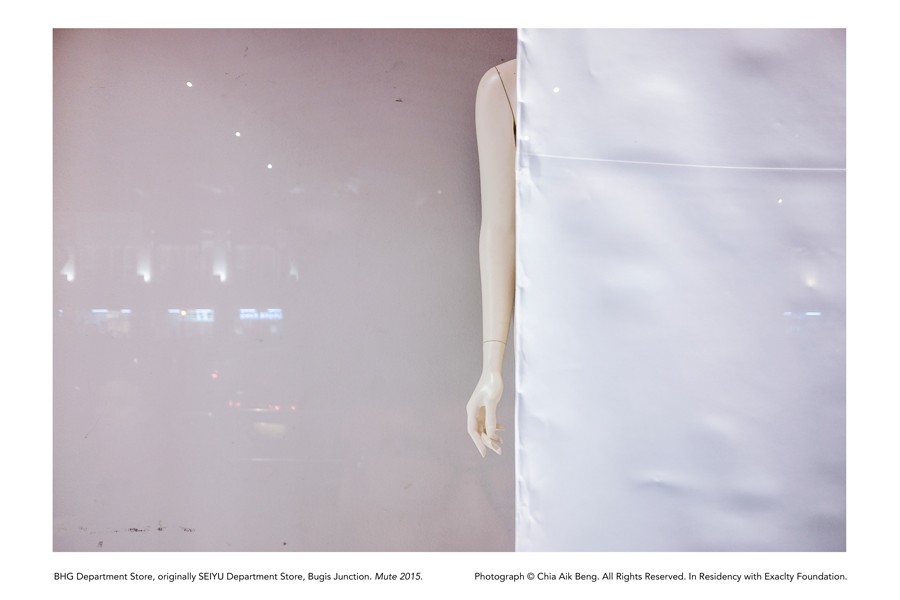

Fast forward to late 2015, I read James Francis Warren’s Ah Ku and Karayuki-San: Prostitution In Singapore and came to know that there was a Little Japan in Singapore, between late 19th century until the end of World War II. What caught my attention about Little Japan was the presence of Japanese prostitutes known as karayuki-san. They worked in mostly Japanese-own brothels in the area of Middle Road, Hylam Street and Malay Street … where Bugis Junction is today.

I was very curious to find out more about how the karayuki-sans lived. After reading Warren’s book, I was overwhelmed by the fact that these karayuki-sans have been forgotten, erased from history. These questions lingered in my mind: “Why are we not told?” “What happened to them after World War II?” Questions that led me to want to discover not only more about them but also about Little Japan and all that disappeared from Singapore’s cityscape after World War II.

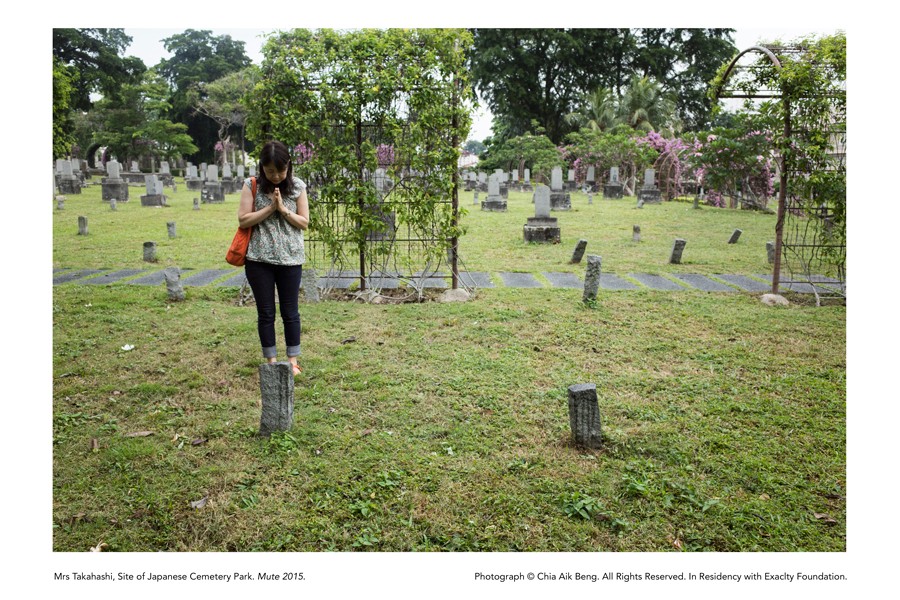

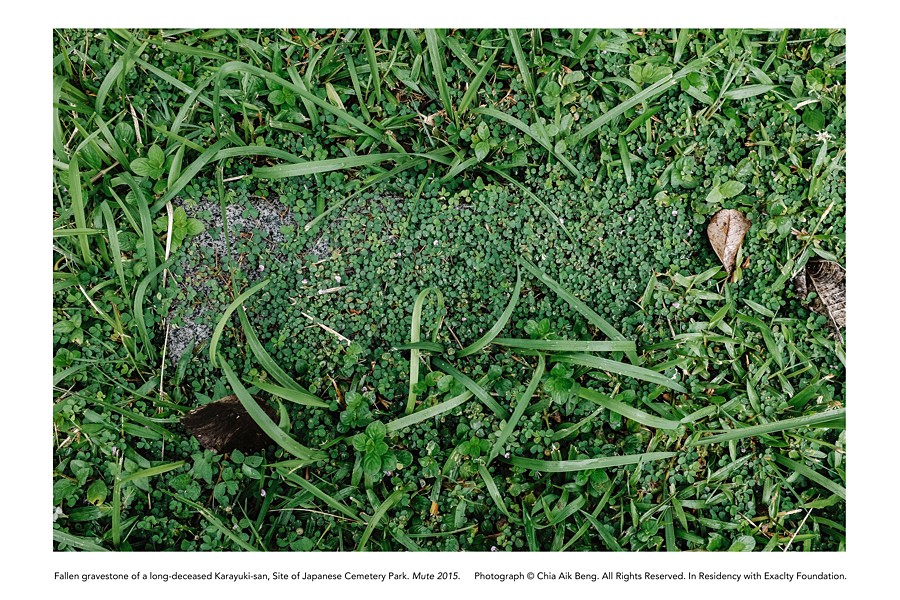

At the Japanese Cemetery Park on Chuan Hoe Avenue, where I started to spend most of my time for this Exactly project, I immersed myself in imagining a karayuki-san’s journey from the beginning to the end. Forgotten by society and especially now by us present-day Singaporeans, I felt sad as I walked and sat around at the cemetery.

My meeting Mrs. Sato and Mrs. Yuko Gan were the most memorable encounters, which were filled with joy and sadness when they shared their stories with me. It was clear there was strong sense of loss as well as belonging. Mrs. Sato so missed her childhood home on Mt. Emily that even touching the wall was done with great tenderness. Mrs. Gan recounted that while feeling homesick for Japan during her first year in Singapore in 1967, she was filled with joy meeting an elderly lady, dressed in a sarong, who spoke her language; she found out later that the lady was one of the few remaining karayuki-sans in Singapore. In our West Coast area! My grandmother lived in that area! I grew up in that area!

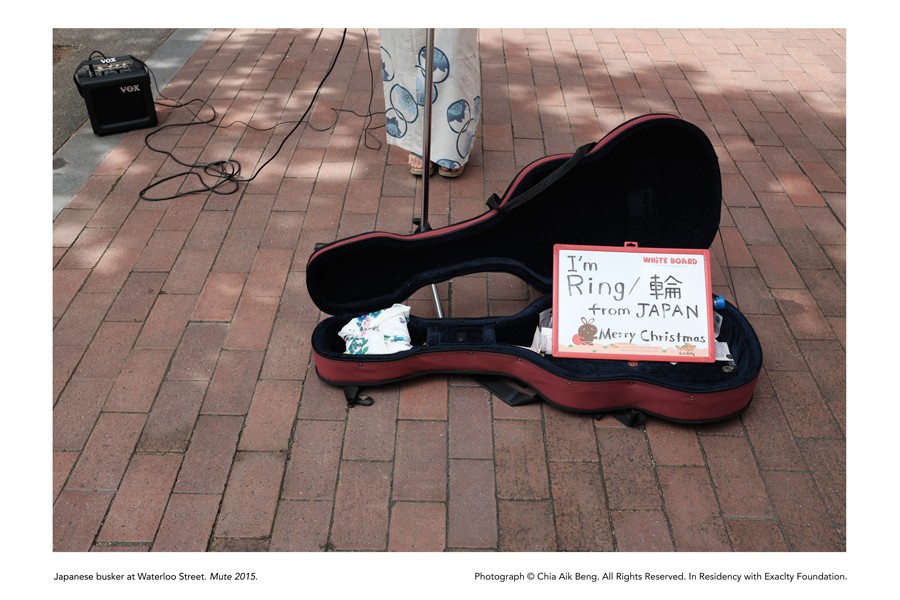

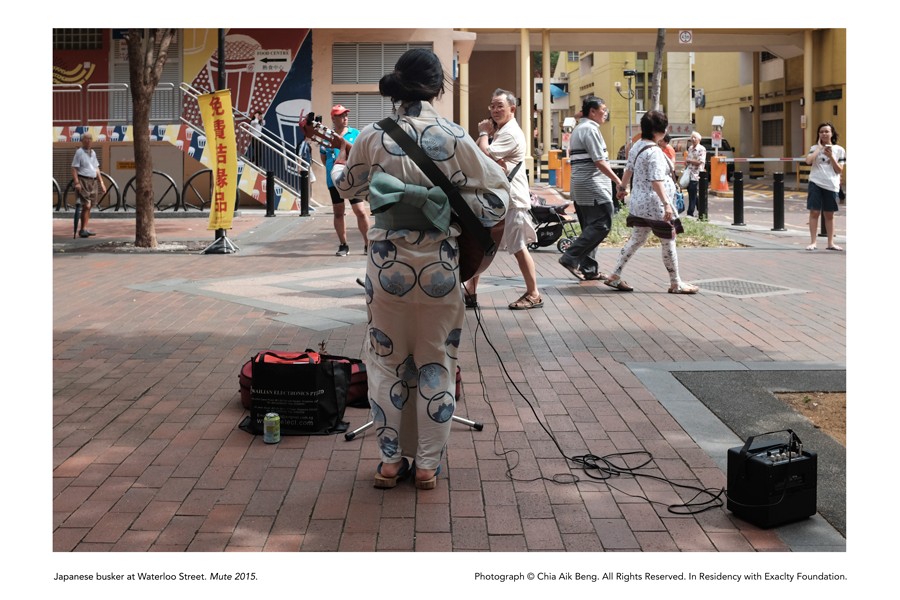

My biggest challenge was dealing with Bugis Junction. Knowing its past as a major Singapore red-light district until 1930s, my question was: how am I going to capture images that represent its past history? There is nothing left to show that. All those shoppers, do they know the history of Bugis Junction?

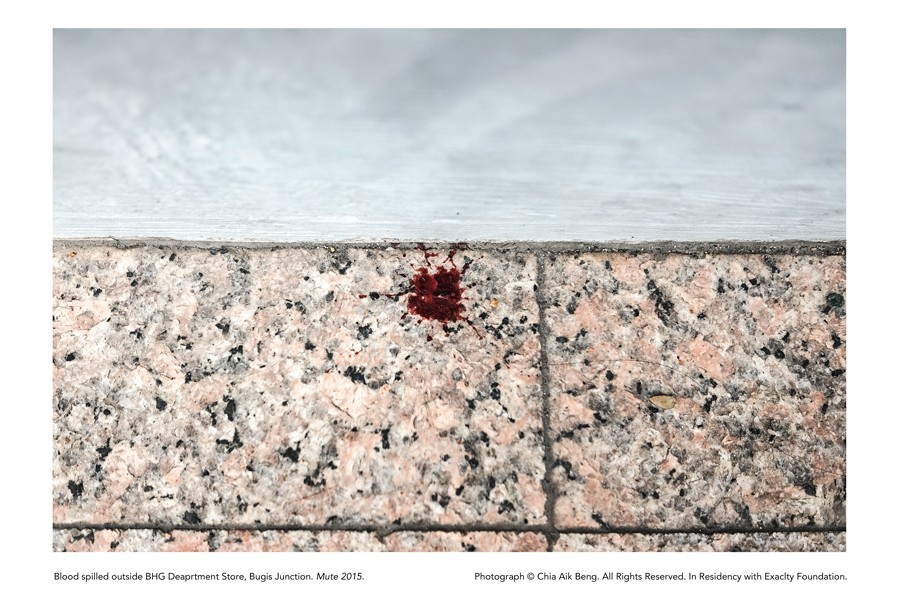

There was one photo-shoot when I stood at Bugis Junction, thinking: the past has disappeared. I thought about the blood spilled in that part of Little Japan where men fought over karayuki-sans, karayuki-sans committed suicide, many died of illness.

And right at that moment, a fight broke out in front of me and blood was spilled … again … today !

So maybe it hasn’t all disappeared.

Being a street photographer, I have spent most of my practice capturing moments at an instant. Sometimes I don’t even know the subjects I photographed or the stories behind the subjects.

But making Mute was different. It wasn’t about capturing moments in an instant. Instead, Mute gave me moments of being alone … to reflect, to think, to question, to seek and to understand.

Word from the ‘Wart[1]

19th March 2016

I must have seen photographs of Little Japan’s karayuki-san a dozen times in the National Museum’s former Photography Gallery, but it didn’t hit me until Exactly’s first resident-photographer Kevin Lee and I had a Bras Basah’s history tutorial with Mr. Ng in April 2015 … that I’m NOT looking or thinking properly.

Our chat went like this:

…and these were the Japanese prostitutes, karayuki-san in Bugis.

When?

1920s and earlier.

What?!!

Who owned the brothels?

Many Japanese owned.

(another) What?! Bugis? Bugis Junction? Really?!!

Chia Aik Beng’s Mute project is not just about documenting Bugis’ history or reviving less-known history. That’s just a starting point. Exactly’s projects are always transformative gestures … aimed at viewers, in the hope that change in a person comes from change in thinking. Photography then is Exactly’s chosen medium with which the photographer helps us to see differently, helps us to land on an issue worth discussing.

We roughly know Singapore’s Bugis area’s residents to be 17th -18th century Bugis-Malays from Sulawesi and 1960s’ transvestites … what was going on in Bugis in the 100 years in-between?

There in Bugis 1860s-1945 was Little Japan. The issue then is “why do we NOT know?” Have we forgotten? Or are we NOT paying attention or were we NOT told? Or do we just NOT care?

I went into a tailspin of “what’s” – what are we really looking at?

The who-knew moments I had led to a “so what’s changed?”. Aik Beng’s Mute references Little Japan in Singapore 1860-1945, which included a red light district of more than 100 Japanese-owned brothels with 1000-some Japanese prostitutes, 1870-1920. The women were mostly impoverished young Japanese women trafficked into Singapore to serve the many low-cost, unaccompanied male labor. One angle for segregating this business in the Bugis area was the British colonial government’s decision to control diseases and maintain law & order among a predominantly male community where male-female ratio is said to be as high as 6:1. Another story is the Japanese women being told that they are performing an important duty: allegiance to the Japanese emperor as their pillow talk/walkabout gathers military intelligence for Japan’s expansionist plans! It is estimated that these women’s repatriated funds back to Japan was the third largest foreign exchange earner for the Meiji govt. Another tidbit: around 1894, the Japanese introduced to Singapore the jinricksha, a two-wheeled passenger cart pulled by a person on foot, still considered post-card prettiness of old Singapore, which soon sprouted the Jinricksha Station in the Middle Road area. By the start of the 20th century, the number of Japanese residents increased substantially to 6,950.[2] So what’s changed in Singapore today? We still have unaccompanied/low-cost male labor and prostitutes from desperate countries and red-light areas like Geylang … except the nationalities are different (South Asian/China temporary workers, South-east Asian/Chinese women). The point is: Little Japan was a vibrant economy before end-WWII with flower/fruit/sundry shops, department stores, printing presses … dentists and major textile shop Echigoya that even the non-Japanese regard as destination sites. Middle Road was Chuo Dori or “Central Street”[3] … when Orchard Road was still “in the sticks” (countryside). Today’s Geylang is more than a red light district: it’s food, Buddhist amulets, fortune telling, durians! Yet, so few of us Singaporeans know or think about these “foreign” men and women especially those “invisible” to us, much less even willing to acknowledge their contributions to Singapore’s economic success then … and now.

What’s missing? There could well be among us descendants of the Japanese karayuki-sans, but their ancestors’ names and identities have been obliterated. The women not repatriated back to Japan after WWII “disappeared” by marrying Malay or Indian men, not likely Chinese men (given the Chinese WWII animosity of the Japanese). We hear that these women became dark-skinned from the tropical sun, wore sarongs … just to blend in. This is like a new “type” of Peranakan, no? If I mention this, I’m sure I would get quizzical looks. Why are we so sensitive? I chatted with an Australian friend, long-time resident of Singapore that this would be like the story of extreme difficulty in documenting the descendants of the Indian convict labor (whom the British brought in to build our many major monuments e.g. Istana, Parliament House/Supreme Court now the National Gallery and yes, the St Andrews Cathedral) … because it’s so “embarrassing”. He started laughing: “well, we don’t have that problem in Australia. If we don’t own up to our convict past, many of us won’t have a thing to say about our family tree”.

Finally, I landed on “so what?”

On Bugis as an area … or rather Bugis Junction and today’s Middle Road … I learned a new phrase from reading about post-WWII acknowledgement and compensation to Korean comfort women: spatial politics of resistance.[4] That monuments in Seoul commemorating the plight of these women are also sites of knowledge production as well as protest. That space in and of itself is contestable. However, the obliteration of signs of injustice in a place such as the Bugis area just makes it so much harder to figure out just what our discomfort and disagreement are supposed to be.

I also learned another new word recently: self-agency.[5] Such that one would take a position, take action with no regard to political or institutional affiliation, just because it is the right thing to do. Like agency, which is something’s effect on something or someone, except this self-agency is self-generated. Exactly’s projects will always ask you to authorize yourself to assemble the knowledge. Because all that information is readily available, see footnote.[6] We just have NOT engaged. I would like to think that Mute confronts you to be curious, and not to “de-curious” after leaving the viewing.

In short, Mute invites you “to take your ignorance seriously”[7]. I regard Mute as coaxing us to taste self-agency. Isn’t it time we feed ourselves?

[1] ‘Wart is short for Stalwart, which Exactly Foundation’s first resident Kevin Lee suggested that for future residences, I should pen a statement as “Exactly Foundation Stalwart”. Thought that label carried too much adult responsibility.

[2] Mikami, K. Pre-war Japanese community in Singapore: Picture and record. Singapore: The Japanese Association, 1998. pp 26-27.

[3] Lai Chee Kien. “Multi-ethnic Enclaves around Middle Road: An Examination of Early Urban Settlement in Singapore”. Biblioasia (Vol 2, Issue 2, 2006). Singapore: National Library Board.

[4] Lee, Yeo-Hyeok. “Towards ‘Translocal’ Solidarities: the ‘Comfort Women’ Issue and the Spatial Politics of Resistance”. Localities. November 2015, Volume 5: 159-169. Korean Studies Institute, Pusan National University

[5] Ho, Kwon Ping. Ocean in a Drop. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Pte. Ltd. 2016. pp 23-24. Ho refers to the 400 young parents who gathered at the National Library Singapore in 2014 to read to their children the banned And Tango Makes Three (“gay penguins” children’s book about two male penguins who adopted a baby); and the 26,000 at Pink Dot 2015 who gathered “… not to oppose the government but to celebrate the increasing diversity and self-agency of civil society”.

[6] Suggested sources:

- Photographs online, in National Archives, National Museum. As well as websites from Japan.

- Lam Pin Foo. Whatever Happens to the Pre-war Japanese Community in Singapore? December 31, 2012. Longer version of The Japanese Were Here Before the War, published by Singapore’s The Straits Times on 25th February 1998. https://lampinfoo.com/2012/12/31/whatever-happens-to-the-pre-war-japanese-community-in-singapore/

- Re-enactment video https://vimeo.com/54590408 Singapore, 1891. The Karayuki-san (“women who went overseas”). Japanese prostitute. Produced by M’GO Films for the National Museum Singapore, 2006. Adapted from historical source. Agency: gsmprjct°. Accessed: 28 February 2016

- Musical Broken Birds by Theatreworks, performed at Fort Canning Green, Singapore, 1-18th March 1995. Short version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qMCnWbGrZ_A. Longer version and explanation: http://www.theatreworks.org.sg/archive/broken_birds/index.htm

- Prewar Japanese community in Singapore: picture and record (pp. 36-41, 64-65, 82-91). (1998). Singapore: Japanese Association. And many other books at the Japan Association.

- The seminal book by James Warren, Ah Ku and Karayuki-san: Prostitution in Singapore, 1870-1940 (http://nuspress.nus.edu.sg/collections/singapore/products/ah-ku-and-karayuki-san?variant=1245097780)

- Edmund Yeo. Karayuki-san: The forgotten Japanese prostitution era. 6th October 2011. http://www.edmundyeo.com/2011/10/karayuki-san-forgotten-japanese.html

- Takehiko Kajita. Singapore’s Japanese prostitute era paved over. In Japan Times 18th June 2005. Updated: 20th June 2005. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-06/20/content_452908.htm

- Japanese documentary: Karayuki-san, the Making of a Prostitute, 1975 by Shohei Imamura.

[7] Quote from Kodwo Eshun (The Otolith Collective) who curated The Chimurenga Library, a traveling exhibit from South Africa, about self-acquiring knowledge on Africa. http://www.theshowroom.org/exhibitions/the-chimurenga-library