ARTIST’S STATEMENT July 2016

[NOTE: No part of ANY text and material related to

Who Cares? is to be used, copied, published or quoted without written permission from the author(s)]

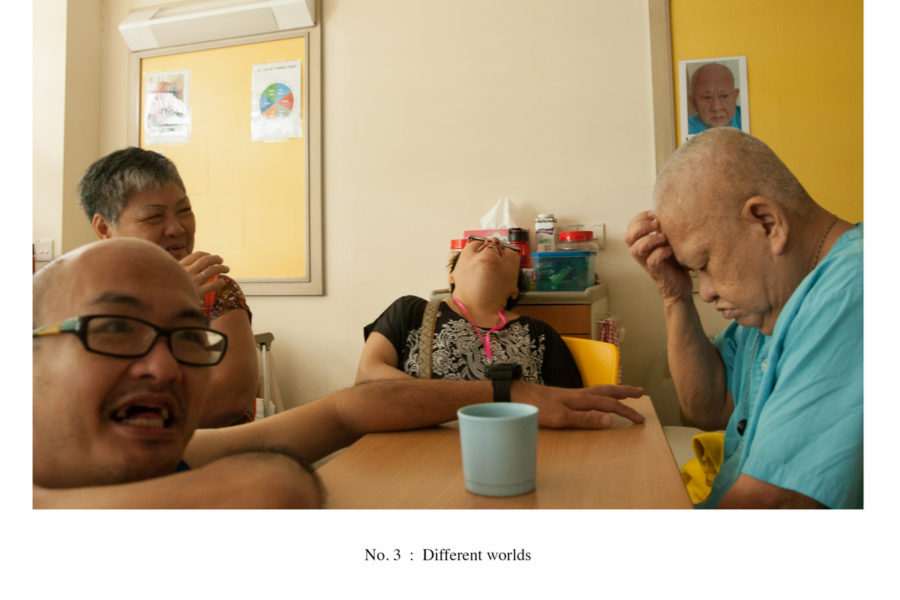

In the eyes of Singapore’s policies, the elderly should be cared for by their children and family members, with foreign domestic workers as a secondary caregiving option.

Do these policies really help the elderly and foster intergenerational bonding?

Who are the real caregivers, what binds them with their seniors, and do our policies play any role in this relationship?

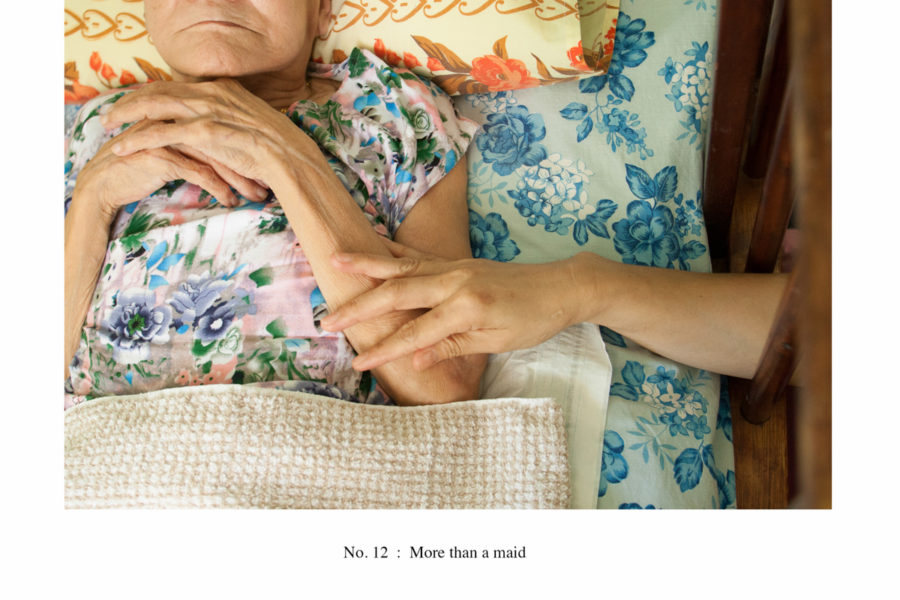

Photograph by Kelvin Lim: Josephine’s caregiver sleeps on the floor beside her. She wakes up every couple of hours to touch her through the bed railing, and check if she’s breathing normally.

ARTIST STATEMENT – Kelvin Lim, 12th November 2016

Who are the real caregivers for our seniors?

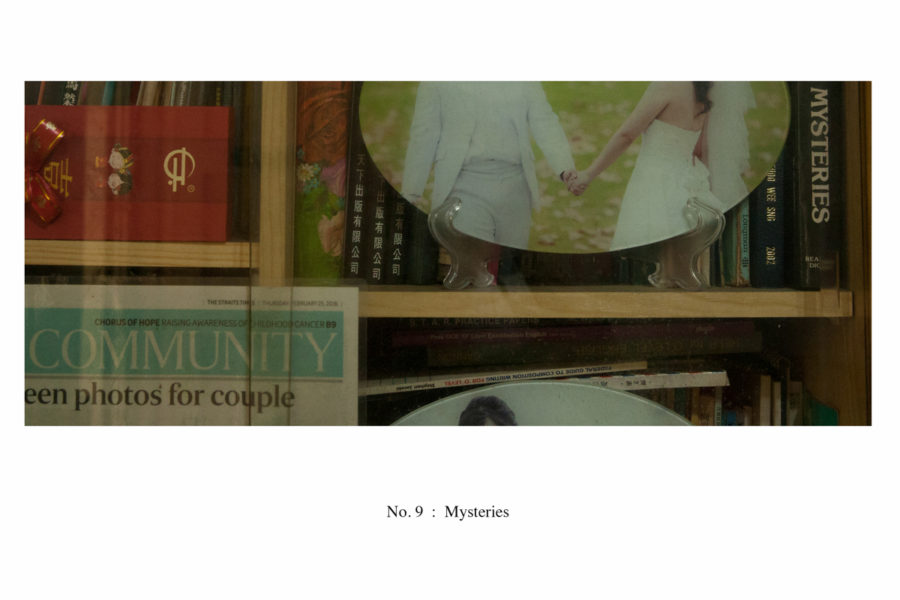

In Singapore, it is widely assumed that the young and “the community” should take care of the old. Even our social welfare policies are shaped by these assumptions. Singaporeans receive generous government subsidies for living near, or with, their parents such as priority queue for HDBs. Time and again, we hear of surveys that most seniors want to stay in their own home. We see childcare centres being built near senior activity centres and nursing homes, included within HDB estates. All to ensure that Singaporeans can provide better care for their aging parents while raising their families.

Are these really the best options for the elderly – bringing the young and old together, expecting the young to be the main caregivers? What if the senior doesn’t have any young?

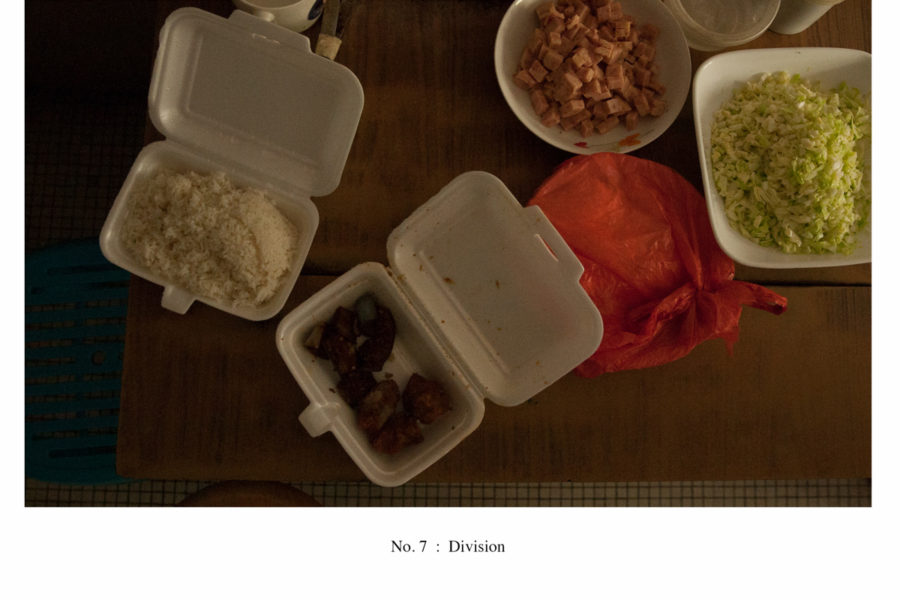

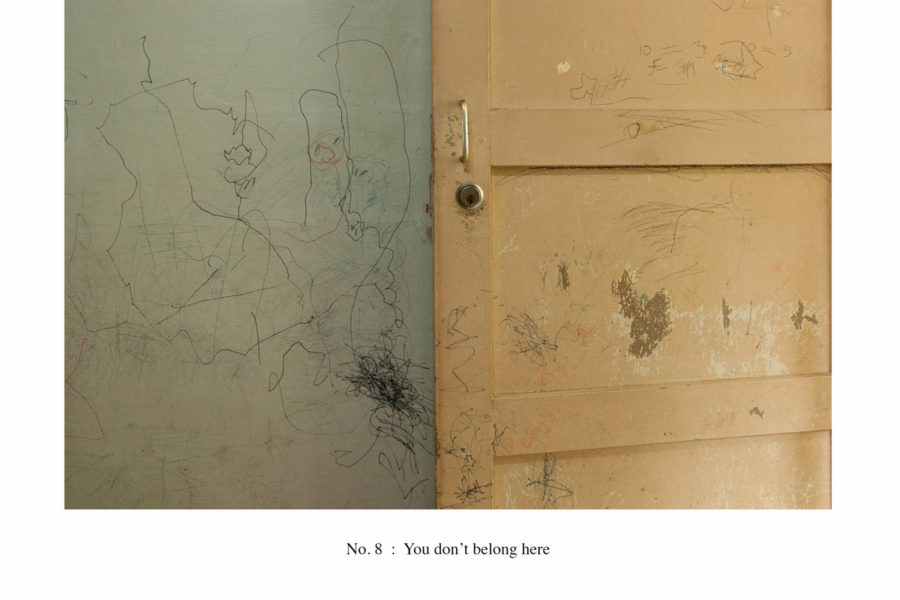

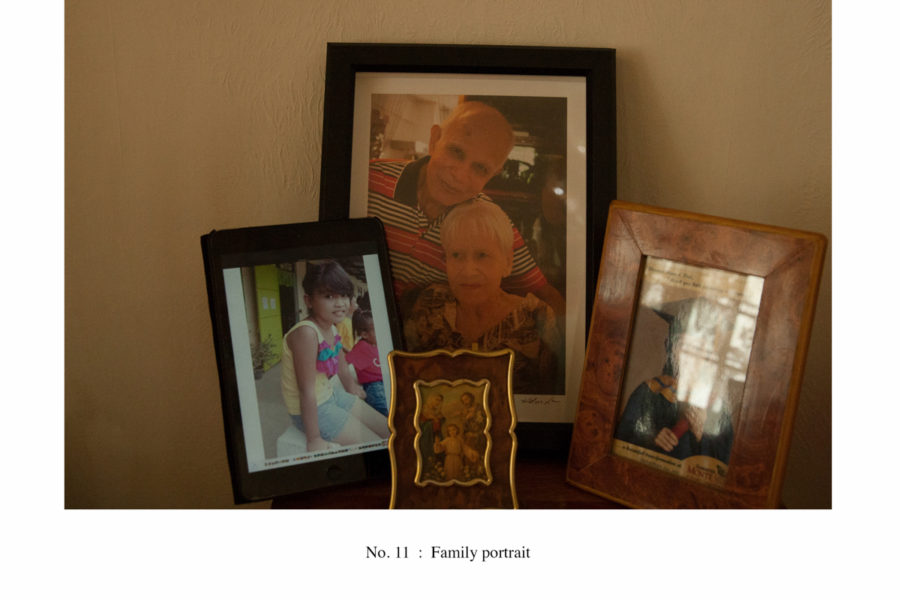

One story I found. An elderly couple lives together with his son and his young family – a beautiful wife and two little children. On the surface, they are Singapore’s model family of three generations under one roof. The reality, however, is a heart-wrenching story of a deeply divisive family bound by duty and hatred.

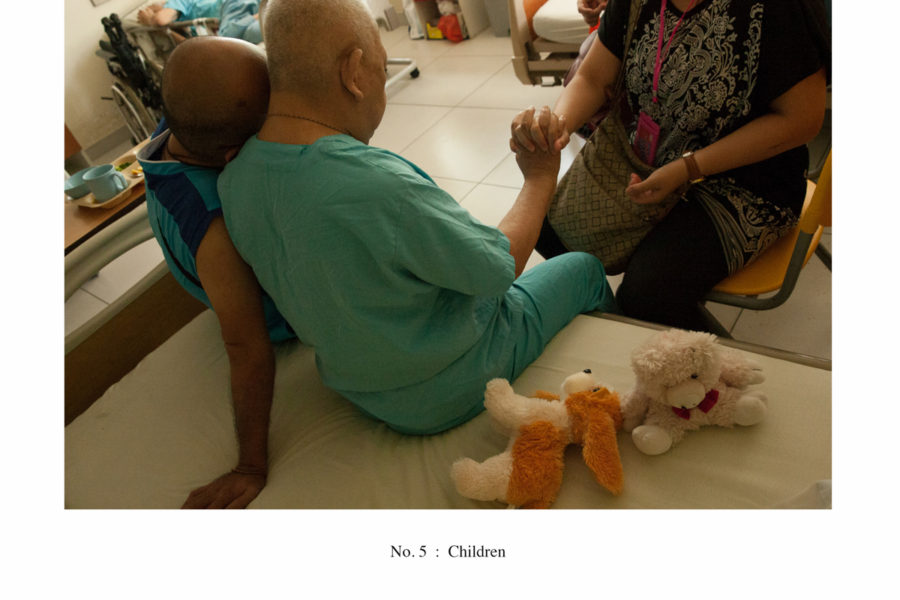

While there are seniors who are dearly loved and cared for by their children or family members, many working adults are simply too busy to provide proper care for their aging parents. To solve this problem, many Singaporeans hire foreign domestic workers (FDWs) – often just called “maids” – as caregivers for the elderly.

However, in Singapore, FDWs are neither recognized nor trained as professional caregivers. To date, there is no official plan (that I know of) to professionalize the job of caregiving by FDWs.

Without proper care by family members or FDWs, who is to take care of the elderly? What options do they have, besides going to a nursing home?

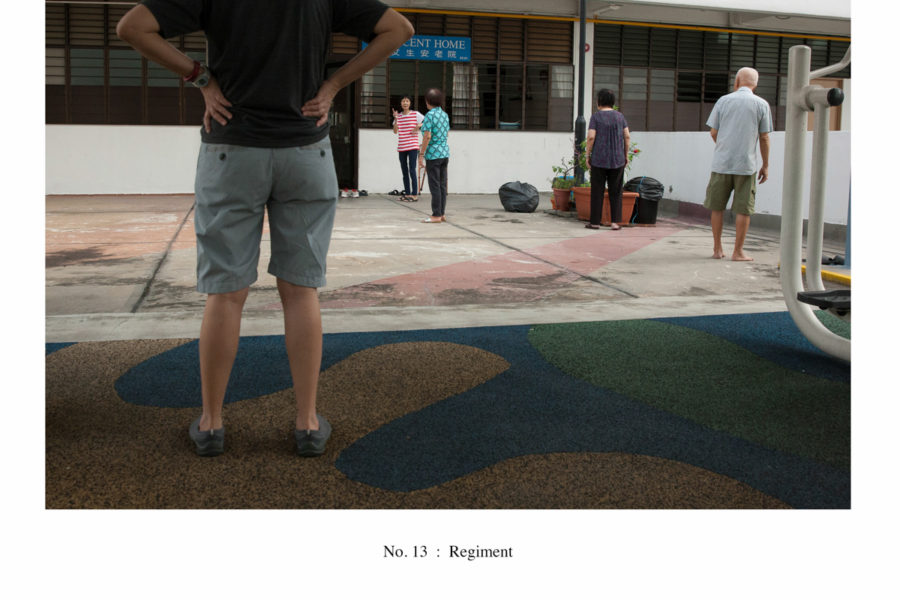

Another story. In a quiet corner of Waterloo Centre — in the heart of Singapore’s commercial district – 12 elderly folks lived seemingly peacefully in a shelter run by a Catholic church. These folks are poor, homeless, and have no family support, but they’re able-bodied and independent. The shelter provides basic needs for them – private bedrooms, shared bathrooms, a pantry, a common area with TV – and a small allowance to buy food for themselves. Besides a mandatory thirty-minute morning exercise every weekday, and a weekly visit by a qualified doctor, the residents are left to themselves.

These 12 folks are among the happiest seniors I’ve met. Despite surviving only on basics, they have enough to eat, are free to do anything and go anywhere. They have friends around them all the time – not young volunteers and social workers, but fellow seniors they can relate to.

This isn’t a nursing home environment, where six to nine patients share a ward, sleep in hospital beds, fed regimented meals cooked for hundreds of “patients” en masse, and are confined in a walled community controlled by nurses.

Why aren’t there more options for our seniors to age with dignity?

“Despite the years of discussion, long-term private and public residential care options for the elderly are limited. For many frail elderly people who live with family without the necessary time or nursing expertise, or for those living alone who are unable to hire a full-time helper, nursing homes remain their main option.”[1]

As Singapore continues to advance as a first-world nation, there remains a gap between our “modern world” and the aging population. A void persists between a generation driven by statistics and a community of seniors and seniors-to-be who need – and want – to be understood. What we understand now may not be relevant in 2030, when our land will be swarmed by almost a million elderly people who need our care. We must plan for a future generation of seniors with very different needs: seniors with different dreams, seniors connected to a virtual global community, seniors who value the power of choice.

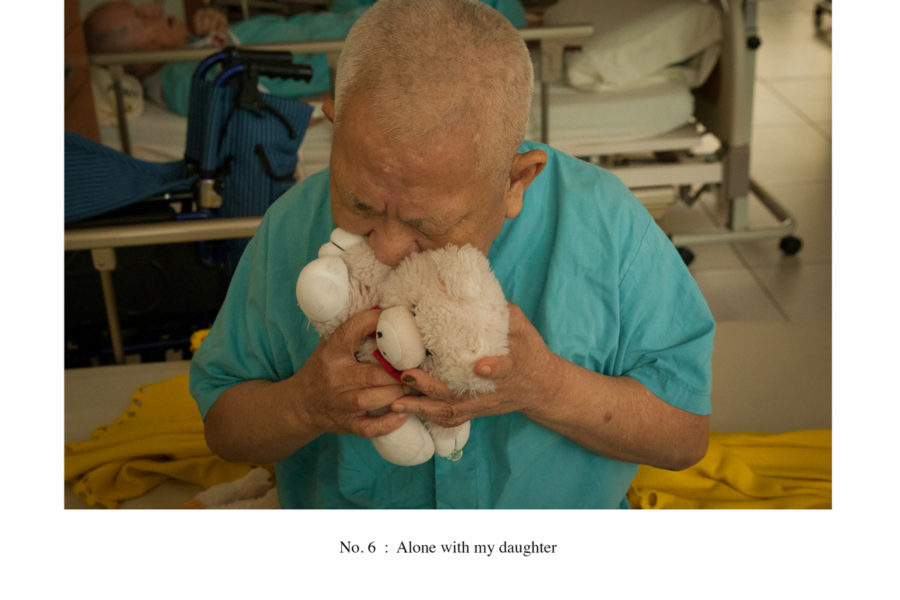

I am innately driven to understand people. I treasure every conversation with the elderly because their experiences are so rich with history, knowledge and wisdom. When Home Nursing Foundation (HNF)2 called me last year to photograph their elderly patients – a project named “Portraits of Love” – I was elated. This was a great opportunity to empathise and learn from our seniors.

In time, “Portraits of Love” morphed into a large-scale project to publicise HNF’s services. This was wonderful for the aging community as HNF has improved the lives of many seniors. However, this also meant that we could only publish photographs and stories which fit the project’s purpose – happy seniors.

I wished I could have done more. Many seniors wanted to be heard and understood. How can we understand and help them, if we only hear a select part of their stories?

For this reason, I am extremely grateful to be working with Exactly Foundation on Who Cares?. Instead of stifling creativity and free expression, the Foundation encouraged me to dive even deeper into the seniors’ stories, resulting in a much more profound understanding of their needs.

The most important experience in this project, for me, is stepping out from the emotional depths of the elderlies’ stories and asking pragmatic questions on what elder-care really means. It is through this experience that I feel empowered to engage in effective conversations, ask good questions and discuss solutions for our seniors.

When our time comes, can we all age with dignity and grace? And how?

Footnotes:

1 “Growing old: Should you be worried?” by Janice Tai, The Straits Times, November 5, 2016

2 A non-profit organisation that provides home nursing and medical care for home-bound patients.

WORD FROM THE ‘WART[1] – Li Li Chung, 12th November 2016

From “my bed” to a hospital bed. That more or less sums up the choices of the Singapore elderly, either you live at home or you go into a ward.

But isn’t there, shouldn’t there be … more choices in-between one’s capacity to manage oneself in one’s own home (or in a relative’s home) and a big ward-like room shared with many others (who most likely are strangers and have the same need for institutional care)?

Singapore nursing homes have bad PR, we think of them like dog shelters … inhumane, not clean, bad food, overworked staff … for the homeless … the last resort where someone likely viewed and wracked with feeling un-filial would put their elders.

I’m not talking about the elderly who are poor, disabled or the “vulnerable adult”. I’m talking about us, the masses – the average Singaporean elderly, poor and rich, aged 55 and older. What about the HDB residents who don’t make the “assistance” cutoffs? What about those in private housing? Aren’t we citizens, too? If there are alternative options, what are they?

I’m talking about the years of any elderly’s life, aged 55 and beyond. The years between one’s own bed at home and the hospital bed.

What do we really understand about aging? My mother is 97 and in a Taipei nursing home since her mid-seventies when dementia started showing up. All her three children live abroad; her husband had passed on long ago. In her twenty years of living with dementia, I have seen her condition change over time and each step of the way, her care needs are slightly different. One constant: caring for the elderly with dementia takes a huge amount of patience and sensitivity. Now that she’s immobile, a huge amount of physical strength is required to lift her to/from bed and wheelchair. She’s now like a new-born: barely a sound, five cans of liquid food, ten diapers a day … sleep, sit, shit. She wasn’t like that in her seventies.

Try as I want to, I’m not capable of being my mother’s caregiver. If my mother lives in Singapore, the government and society here would say I should stay home and take care of my mother. If I can’t, “hire a maid”. Any ole maid, the same category of foreign domestic worker (FDW) labeled as “unskilled labor,” who cleans our homes. Basically any warm body who can feed porridge. Why like that? Because a caregiver for the elderly in Singapore is still not considered a respected occupation. It’s not even a separate foreign labor category. Don’t we need to be mindful of “para-nursing” qualifications? She needs to read English medicine labels, no? What’s her career path? All employers can do is rely on wits and common sense in the hiring process. (My mother’s caregiver in Taipei is certified — licensed like an insurance agent.)

Why are we like this in Singapore? Because to have choices of elderly care options, one must get the thinking right. And broad. We must also have infrastructure (e.g. in 2013, we have “… more than 99,000 childcare places … compared to around 3,000 for day-care services for the elderly.”[1]). The second is operating principles (the key word is principles): one size cannot fit all. Thirdly, people. The “right” people. Qualified people: professionals, not volunteers i.e. not over-reliance or insistence on family members, a topic that has not escaped an observant visitor.[3] This is much more serious than being neighborly.

It is also not just about funding or resources. There is a myriad of good-intentioned public and private organizations all participating in making life better for the aging. Ministry of Health in 2016 published an 80+ page I Feel Young in My Singapore! Action Plan for Successful Ageing. [4] One key assumption is probably best summarized in Chapter 4’s title Kampong for All Ages sub-texted by “Singapore must be a cohesive community where seniors can age actively and happily”. Yes, all true and good but how and till when? Who’s the on-site, the reliable and the personal caregiver?

Are we spending tax money, time and effort in the right places? By 2030, it is estimated that Singapore will have 1:4 (25%) of people who are elderly … and many will be living alone and female. Do I as one in the post-55 group only need visits from social workers, a really jazzy exercise program, meet new friends while planting home-grown vegetables? While I can still make my own decisions, don’t I need a plan on where and how I would like to live as I age beyond my own capabilities to be independent? With all the advisors offering retirement planning (wealth management, insurance), where are the advisors on aged care?

Where else can I live? And how?

Footnotes:

[1] ‘Wart is short for Stalwart, which Exactly Foundation’s first resident Kevin Lee suggested that for future residences, I should pen a statement as “Exactly Foundation Stalwart” — thought that label carried too much adult responsibility.

[2] “Singapore’s caregiver crunch”. The Straits Times. 27th September 2013.

[3] Rosa Kornfeld-Matte (UN Independent Expert on the enjoyment of all human rights by older persons) in a 29th September 2016 press conference after her weeklong visit to Singapore said, “In the area of healthcare and caregiving, she noted that there are many volunteers involved in supporting the elderly. However, she added that caregiving should not be wholly dependent on volunteers and the state should be the main entity in the provision of care. On a similar note, she agreed that the family plays an important role in caregiving, but again stressed that the state must be present to support the family”. Chong Ning Qian, AWARE Research Executive. UN Expert to Singapore: offer more state support for eldercare, pension for all, minimum wage, poverty statistics. October 3rd, 2016

[4] https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/dam/moh_web/SuccessfulAgeing-WCMS/action-plan.pdf